Conclave's Error

Confusing prayer and divination

Cardinal Thomas Lawrence casts his ballot for the next Roman Pontiff. He has just sworn an oath to Jesus, in Latin no less, that he has voted for the man he believes best. But he doubts. Cardinal Lawrence knows the process that led to his decision. He witnessed the politicking and scheming of his brother cardinals. He schemed and politicked himself. Is the name on this ballot really the man he believes best? Or is he lying to Jesus?

An explosion rocks the Sistine Chapel, replacing Cardinal Lawrence’s inner turmoil with outer chaos. Has God judged Cardinal Lawrence for his decision?

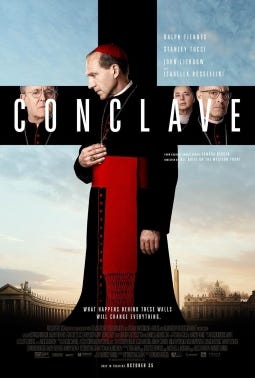

Much ink has already been digitally spilled over the excellence or travesty of Conclave (2024). The protagonist, Cardinal Thomas Lawrence, played by Ralph Fiennes, is the Dean of the College of Cardinals and must manage the conclave to elect a new pope. The film is heavy on back room dealmaking and light on spirituality. Ralph Fiennes has the acting talent to nearly birth aa deep reflection on the experience of prayer despite the film’s disinterest.

The chief criticism I have seen focuses on the one dimensional caricatures in the film. Cardinal Tedesco, the right wing populist, believes in Western culture and imperial Roman traditionalism, but more importantly stopping the Muslims. Cardinal Bellini, the 21st century progressive, believes in liberal stuff, but more importantly stopping Cardinal Tedesco. Cardinal Adeyemi believes in becoming pope. Cardinal Tremblay also believes in becoming pope, but knows how to spend money. Cardinal Benitez is a Mary Sue.

In contrast, Cardinal Thomas Lawrence, the Dean, the man in charge, is the complex character with an inner life. Like any Catholic character with the name Thomas, he has doubts. As an honorable man, he had tried to resign his position as Dean. The late pope refused his resignation. As an honorable man, Cardinal Lawrence strives to manage the conclave well. But his doubts persist. Interestingly, he specifies that he doubts not God’s existence, but prayer.

Thus the film opens a small door to an exploration of the interior life which Ralph Fiennes has the gravitas to exploit. The film focuses on sordid back room dealmaking, personal and political distastes of the electors, and scandal mongering. Cardinal Lawrence describes it accurately as reminiscent of an American political convention. The caricatures and the powerbroking neither bored nor offended me, for they enabled Ralph Fiennes to bring to life a question that everyone must wrestle with: What good is prayer when I am surrounded by such obviously ungodly behavior?

Regrettably the film itself has no interest in this question. Prayer is an internal experience. True, it has external components, and is sometimes communal. But in essence prayer is “the lifting of the mind and heart to God.” (Dictionary of Scholastic Philosophy, p 95) Generally it is mundane and repetitive, and almost never flashy. It lacks the visually stunning, technically impressive display Hollywood prefers. Divination in some form or other suits the predilections of filmmakers much better. Rather than an internal lifting of the heart, divination seeks to discern messages from God (or the gods) externally through some ritualized action. Different cultures have different methods. Some read the flight paths of birds or cut out animal organs to read the secret missives of the spirits or gods. In Conclave, God is supposed to speak through explosions.

There was a time when God spoke through external signs. The sailors drew lots to determine that Jonah was at fault for the great storm (Jonah 1:17). The Apostles drew lots to elect Mathias as successor to Judas (Acts 1:23-26). This New Testament election by lots offers no support to Conclave’s interest in such visually dramatic methods of divination for papal elections though. The casting of lots has ceased:

Nevertheless, we are in a new world! At the beginning of Acts, lots are drawn to see who will take the place of Judas. But after Pentecost, lots are drawn no more. The Church, guided by the Spirit, meets in Acts 15 to discuss and take decisions about its life and mission. (Cardinal Timothy Radcliffe, Questioning God, p 195)

The voice of the Holy Spirit is to be found inwardly in prayer, and externally through discussions, disputations, and deliberations with others in the Church. God is not distant, communicating through lots or other cryptic tools of divination. The descent of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost confirms the prophecy in Jeremiah 31:33 and inscribes the New Covenant on the human heart.

This is why the unspiritual caricatures of Cardinals Tedesco, Bellini, et alia do not bother me. God acts through human beings as they are and transforms them over time. He does not wait for people to be perfect. It is not uncommon to compare modern failures and sins in the Church with the with the Holy People™ of the Early Church. It is certainly not bad to look to our ancestors in faith. But it can be easy to fall into the temptation of following Conclave in creating caricatures, if slightly more pious, of the men and women who followed Christ in the first centuries AD. Peter and Paul were holy men who responded to God’s call in and through their weakness. They were not Holy Men™ who neither struggled nor suffered as they breezed through a serene quest of success. As Acts 15 attests with the authority of Divine Inspiration, intramural conflict and argument in the Church began amongst the Apostles themselves. We ought to take heart, then, for our own quarrels do not demonstrate a corrupt deviation from the Early Church but rather a continuity of its earliest traditions!

Conclave could have been a film exploring Cardinal Lawrence’s relationship with God in the midst of the type of arguing that has always existed in the Church at every level. Even if one is unwilling to contemplate that the Council of Jerusalem in Acts 15 might have had some unscrupulous participants, there are plenty of stories throughout the Church’s history that make the film look like a pleasant tea party. We often forget or dismiss such stories from our own history, and great art brings such pressing questions to life for us. Conclave was not the film to do that.

Where it errs, specifically, is giving primacy of place to the politicking of the characters. A political conclave could b e an excellent topic for a film but would require all the major players to be complex and three dimensional. As caricatures, their proper function is as tropes to enable Cardinal Lawrence to doubt, to decide, to second guess, and resolve his role as Dean while simultaneously teasing out the complexities of prayer when overwhelmed with responsibilities and displeasures. Cardinal Lawrence’s doubts would serve as an excellent focus for a universal experience for believers: Why can’t I see God here? Why am I stuck dealing with these people? Why won’t God answer me? Instead, Conclave drops the ball and insists that the election of a pope must Mean Something Profound.

Ralph Fiennes picks the ball up because he is a talented actor. The best scenes, with one exception, involve Cardinal Lawrence struggling with prayer alone. When Cardinal Lawrence attempts to pray in his room by himself, the audience sees a man unsure if anyone is listening. It is a simple scene, but carries great emotional and spiritual weight. In another scene while shaving and staring himself down in a mirror, Cardinal Lawrence vents his frustration and orders himself to manage. He must manage the conclave, but also manage himself as he negotiates personal and professional anxieties and, yes, doubts. As he wrestles with himself he wrestles with God. The character may not recognize it, but an audience attuned to Cardinal Lawrence’s inner life can perceive it. The best scene in the film, the exception, comes as Cardinal Lawrence delivers crushing news to Cardinal Adeyemi. The devastated cardinal asks the doubting cardinal to pray with him. Agreeing, sitting next to him at the foot of the bed, Cardinal Lawrence prays with him. It is a brief moment. Cardinal Lawrence’s personal doubts yield to his compassion for his suffering brother. This, not the explosions, is where God speaks in the film.

It is a shame that the film does not give Fiennes more opportunities to explore Cardinal Lawrence’s prayer life. He managed to touch on real depths of spiritual experience in just a few scenes. Conclave thought, incorrectly, that the meaning of the film resides in the selection of an absolute monarch. That is the preoccupation of the world dipping into Catholicism for its weirdness and aesthetic. To be fair, the weirdness and aesthetic of the Church can do a great deal of heavy artistic lifting. Truth has a way of shining, though, even when it is abused. The meaning in Conclave resided in the silent struggle of an individual soul persevering in prayer. Ralph Fiennes gave that performance, but the film mistook divination for prayer, and politics for profundity, and in so doing denied its own lead actor an Oscar.